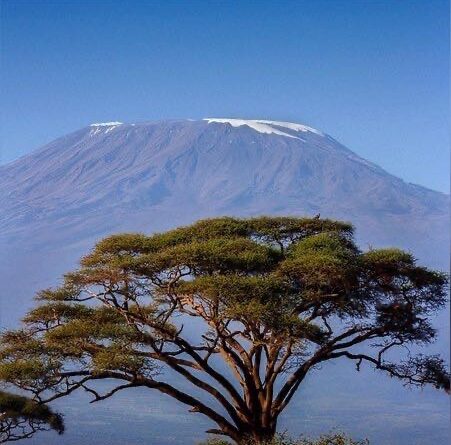

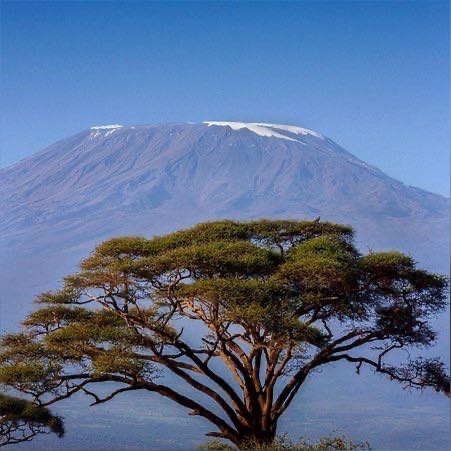

Reflections on Kilimanjaro

It’s 22 September 2022. I’m standing at the top of Kilimanjaro, totally exhausted, freezing cold and worried that I am about to go blind. This is the short story of how I got there, and what happened next.

I’ve been a supporter of the tax charities, TaxAid and Tax Help for Older People, for many years. In 2019 I heard there was a plan to climb Kilimanjaro to raise funds for them. Intrigued, I attended a briefing by Action Challenge and came away inspired to do it. Before that I knew very little about Kilimanjaro but the trek sounded challenging while doable.

I told my family and my eldest daughter Eleanor said she would like to join too, which was fantastic.

The plan was to do the climb in September 2020 but covid put paid to that. 2021 went the same way. Finally in 2022 it was happening. Sadly the original tax group of about 16 had shrunk down to 5 so we became part of a wider team. The tax team were Tina, whose brainchild the trek was, Rachel, Chris, Eleanor and me. Our tagline was #KiliTax2022 but the rest of the group quickly renamed us Kill Tax!!

And so to Tanzania. Over the first five days we climbed the equivalent of 2.5 times Ben Nevis. Three of these days were tough. Long days with often challenging terrain.

On two of these I became quite tearful when we finally arrived at our camp for the night. On another Eleanor burst into tears at breakfast and then again halfway through the day.

It’s very difficult to convey what made it so hard and, at times, emotional.

The altitude was one aspect. The decreasing amount of oxygen meant that much of the time you had to focus on just breathing as efficiently as possible. Deep breaths in through the nose and out through the mouth. Even that was hampered by the dusty conditions which meant it was best to cover your nose and mouth with your buff. In my case this felt like it was squashing my, admittedly large, nose and so restricting my breathing. Either way, over time we all inhaled so much dust that we were continually blowing our noses to try to clear the airways. And over time we all developed a Kili cough.

Lack of sleep was another aspect. We were up at 5 or 5.30 most days having had a very broken night’s sleep. Trying to get comfortable in a sleeping bag wearing a woolly hat, socks and layers to stay warm was not easy. And we were drinking so much water, to counteract the risk of altitude sickness, that as soon as we got comfortable, more often than not we needed a wee!

And a wee was not straightforward. It involved finding a head torch, opening the tent’s inner zips, crawling out backwards to put boots on, opening the outer zip, crawling out backwards and then zipping everything up again to retain any warmth, then staggering to the toilet tent making sure not to trip over any rocks on the way. Having relieved myself it was then the same in reverse, plus trying to find the hand gel on returning to the tent.

Finally the local support team were UNBELIEVABLE. A truly remarkable group of people. For the 18 of us on the trek, there were about 60 local guys. And I say guys because they were almost all men. But we did have one stand out female guide, Amy, who will live in our hearts forever. She was so positive and encouraging and supportive.

The main roles were guides and porters.

Guides – who walked with us every day. They set the pace to ensure we walked slowly (poleee poleee in Swahili). They carried your backpack if you were really struggling. They encouraged us when we were down. And on summit night they made sure we got there. We all agreed none of us would have made it that night without them.

Porters – who carried everything from one camp to the next. And I mean everything. Our main bags (up to 15kg each), the tents, tables, chairs, food, cooking equipment, gas, chemical toilets, sleeping mats, medical supplies…..and they went ahead of us so that camp was set up by the time we arrived every day. They mainly carried things on their backs or their heads. And while we were struggling to negotiate some aspects of the climb, they would whistle through almost effortlessly. Absolutely stunning.

Not only did they work so very hard, but they generally seemed to be so good humoured too. When the porters came through they would exchange banter with the guides and it usually involved a laugh and smile.

It was all very humbling.

I did ask a couple of the guides about their conditions and they said that the work paid better than any alternatives and that they were very appreciative of the fact that we had chosen to visit their country and, effectively, give them work. Covid had clearly been a really tough period for them as they had very little to fall back on.

One highlight which will live with me forever was the lunchtime before summit night. We were all sat in the dining tent, had just finished lunch and were getting ready to head back to our tents, when all of the local team came in. The main chef was carrying a huge cake and a bottle of fizz. They all started singing “happy birthday” in Swahili. It turned out to be Chris’ birthday. He hadn’t told anyone but somehow the local team had found out and baked and iced a cake at an altitude of 4863m, higher than Mont Blanc, the highest mountain in Western Europe. EXTRAORDINARY PEOPLE.

And so to summit night. The plan was to rest after lunch in preparation for our midnight torchlit trek to the summit. Nature had other plans and our camp was battered by high winds. I lay in my sleeping bag listening to music and podcasts while amazed that our tent hadn’t ripped free of its moorings and sailed off down the mountain. Despite having my extra thick mountaineering socks on I couldn’t get my feet warm. Having a wee was again a notable event. This time, the toilet tent was at an almost 45 degree angle due to the wind. I didn’t really think this through as, midstream, the lid slammed down and I was suddenly pissing onto a closed toilet!

We gathered around 22:30 for final food and prep, all with multiple layers on. Some people seemed to be wearing every piece of clothing they had brought with them. Just before midnight we set off. Eleanor had been suffering with a bad headache all day and some nausea. The team medic had prescribed her some diamox (anti altitude sickness drug) but it didn’t seem to have helped. So I was worried about how she would cope with what lay ahead, as it was daunting without the added burden of a splitting head.

The task was to climb just over 1000m (equivalent to Snowdon( in the dark with just our head torches for light. It was expected to take around 6-8 hours. It’s fair to say that we struggled big time. We inched our way up. Every now and then I would look up and see a chain of lights winding their way up like some weird Christmas tree. Strangely I didn’t find it demoralising to see how far there was to go. The lights were mesmerising and drew me on.

We stopped frequently, for rest, water or snacks. But as time went on our water started to freeze, and my snack bars were too hard to bite into. And we had not slept for around 24 hours. Later our team lead told us it was about -20C including wind chill.

After about 6 hours, I noticed that Eleanor was pulling away from me. She had got a second wind but I was losing my first. I took a few steps then had to stop, lean on my trekking poles and try and get some breath and energy into my fading body.

After another hour, we were just half an hour away from Stella Point which, at 5745m, is higher than the summit of Russia’s Mount Elbrus, the highest peak in Europe. Here I will quote from a guidebook to Kilimanjaro which describes it far better than I can.

“But it’s a painful tear-inducing half-hour on sheer scree. The gradient up to now has been steep, but this last scree slope takes the biscuit; in fact it takes the entire tin. In just about everybody’s opinion this is the hardest part of the climb, when the cold insinuates itself between the layers of your clothes, penetrating your skin, chilling your bones and numbing the marrow until finally, inevitably, it seems to freeze your very soul. The situation seems desperate at this hour and you can do nothing; nothing except keep going. It’s one thing to fail to reach the summit because of altitude sickness; quite another to fail from attitude sickness.” (Henry Stedman – Kilimanjaro, the trekking guide to Africa’s highest mountain, 2021)

Our attitude was not sick but, as the sun rose and I looked around me and up to Stella Point, I realised that my vision was blurred. I could no longer see clearly out of my right eye (as many of you know, I lost my left eye in 2014).

Our brilliant medic Hannah had been with us all the way up. She examined my eye and advised that it was probably a high altitude retinal haemorrhage. Her advice was to descend to a lower altitude and see if that resolved the problem.

I wanted to get down straight away. Our local team leader Daniel, who had been brilliant throughout, advised that the quickest way down was to carry on up to Stella Point, and then down from there. Plus we would then get a certificate! At the time I said I didn’t care about a stupid certificate. In retrospect I’m glad he pushed it. At 07:30 we got to Stella Point, had a photo taken, from which you can see I was not in a good way, then Daniel arranged who would help me back down.

I told Eleanor that if she wanted to carry onto the official summit, Uhuru Peak, then that was fine. This was 139m higher and about another 45 minutes trek. I knew her answer before she spoke. She was coming with me.

So we began the arduous return to camp. Not the way we had ascended but a quicker “ski run” route, with sand instead of snow. One of the guides Frank had my backpack and gripped my arm for dear life making sure that I didn’t fall over as I couldn’t clearly see where I was going.

It took about two hours to reach camp. My sight was no better. It was about 10am. My options were to walk with the team to the next camp, which would take about 3 hours and wouldn’t be until the afternoon, or take the “Kili-stretcher” which would take me down and out of Kilimanjaro national park altogether.

The Kili-stretcher was described as a trolley on one wheel manned by five strong young men. Will, our UK team leader, said it wouldn’t be pleasant and would take about 4 hours.

I didn’t feel I had a choice. I had to get down asap. I did not want to be blind.

So I gathered some things in my rucksack, said my goodbyes, and put my trust in the young men now by my side. What I hadn’t bargained for was that it would take nearly an hour to walk to the starting point for the Kili-stretcher. This included some scrambling down over large rock formations. But I had one guy holding tightly on each arm. Every time I missed my footing, they caught me.

The best way to describe the stretcher would be one of those large trolleys you find in garden centres. Only difference being, this had one central wheel instead of two. To get onto it, they tipped it forwards so it rested on the front end, laid my sleeping bag out and indicated that I should get in. I gingerly stepped into the bag and then had to support my weight by bracing against the end of the trolley with my feet. They then zipped up the bag and tied ropes across me.

I said to them that I had an eye problem so if they could avoid heavy bumps that would be great. How naïve I was!

With everything in place, we set off. The guys started running along while holding each side of the trolley. Anyone in their path got out of the way pretty quickly!

So began my journey to safety. Every so often they would stop to draw breath and swap sides. The guy at the front had the toughest job, particularly when we got to the steep downhill sections. Bear in mind there are no roads. So they were taking me on tracks. These either comprised footpath type routes which were smoothish on the level bits but every few metres had a step down cut into the path. Each one of those was a heavy jolt to my body. Worse were the sections made up of rock with no discernible flat sections. If I laid flat, I felt like the severe bumps were going to break my neck, so I took to using my right hand to brace my head against the movements. At some points, they literally had to lift me down as the drops were so big.

I looked up, often at passing trees, and tried to find somewhere else to go mentally. But the next bone-shattering drop soon brought me back to reality. My sight hadn’t improved, but I noticed that we were still well above the clouds so a long way to go.

After about three hours, I started to think that my sight was clearing. Another hour and I was sure. I could see again, give or take a few dots.

My attention then turned to my spine. I asked the guys how long left. They said another hour. I told them I was better and that I’d like to walk the rest of the way. They laughed – crazy Brit – and just carried on! I called out again. Explained that they were amazing but that I was worried another hour would mean I would need a different kind of medical help. This time they agreed. So I was released and, much to my surprise, relished the opportunity for another hour of walking. By this time I had been awake around 36 hours and had not really eaten much for about 18. But I didn’t care. My sight seemed ok and nothing else mattered.

The next day I was driven back to the end of the route to be reunited with Eleanor and the team so we could step across the finish line together. The local team were there to greet us with some amazing songs and we celebrated together. Then a tip-giving ceremony for all of the local team. Boy had they earned it.

I’ll end this story with DAFT. Eleanor introduced this to me and we ended each day with it.

Discovered – It was far harder than I imagined. Looking down at the clouds (not from a plane) is truly beautiful. Feeling the real effects of high altitude.

Achieved – I climbed Africa’s highest mountain. As a team we raised much needed funds for and awareness of the tax charities.

Funny moment – I wasn’t there to witness this, but one of our team had a crap at the top of Kilimanjaro. The very idea of wanting, and feeling able, to drop several layers of trousers, expose your nether regions to frost biting conditions and let one go, is bewildering. And makes me chuckle every time I think of it.

Thankful for – so much. The warmth, strength, generosity, resilience, good humour and selflessness of the local team will live with me forever. Sharing the whole experience with Eleanor and being there for each other at our darkest moments. Regaining my sight. The many things I take for granted in my everyday life. The love and support of my family.

It is not too late to make a donation to Brian and Eleanor’s chosen charity https://www.justgiving.com/fundraising/Eleanor-Brian