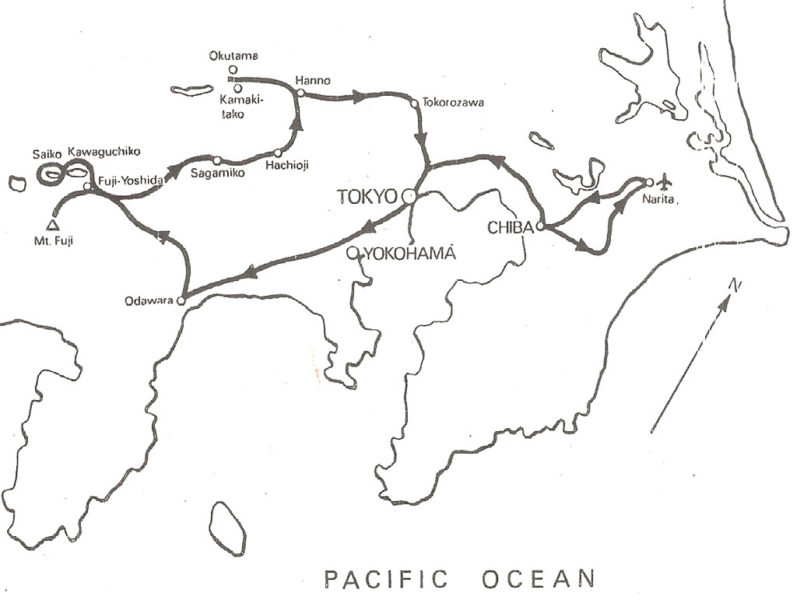

Armed with only a Berlitz Japanese for Travellers phrasebook and a 32 miles to-the-inch Tourist Map of Japan, Meike and I set off from Purley, Surrey, on our bikes for London, Heathrow, about 22 miles away. Meike was on an Emperor Sport, and I on my Leader, 3 Croydon built frame 29 years old.

The Berlitz phrasebook was invaluable at £2, English phrases, equivalent Japanese characters, and phonetic pronunciation — and it did work, rather to my surprise.

Seated in the Boeing 747, Meike and I could scarcely conceal our excitement. Of the 406 passengers, about 370 seemed to be, Japanese, a tribute to British Airways’ image. I asked a young Japanese sitting next to me why he was travelling BA and not Japan Air Lines. “British Airways better”, he blandly assured me, producing a bottle of Chivas Regal and giving me a generous measure. “Scotch whisky very good, too” he smiled.

We landed at Narita airport, about 35 miles from Tokyo, at 3pm, and an hour later were on the road.

After about a mile we reached a fork in the road. No road numbers, and direction signs were all in Japanese script.

At that moment a man with a dog appeared from nowhere. “Eigo o hanashi-masu ka” (Do you speak English?) I asked. Puzzlement clouded his face. “Route e Chiba?” I persevered.

“Chiba!” His eyes lit up, he smiled and pointed to the left fork.

“Domo”, I said. “In fact, domo arigato.” (Domo arigato, many thanks).

We plodded on along a fairly narrow but well surfaced and undulating road, heading south-west for Chiba. Drivers surprised us by driving as though on an economy run; low revs, low speed, courteous and patient.

The sun, which had not set on us for more than 36 hours, suddenly dipped below the horizon.

The youth hostel, about eight miles from Chiba, lay beyond our reach, so we went into town. The day had been hot and sultry but was now turning cool.

By chance we stumbled on a police station. The sergeant swung his boots off the desk. He listened courteously to my request for a place to sleep, then lifted the phone.

Beckoning us to follow him he walked through the doorway and from a cycle rack grabbed a bicycle.

In gathering gloom we rode, up pavements and along them (quite legal), across zebra crossings, until finally the sergeant stopped outside a hotel — Hotel Keissi, it said in English.

With a graceful wave of his arm the sergeant motioned us to enter. My heart sank. “Three star at least”, ran through my mind.

The doors slid apart at my approach and I entered, to be greeted by a smart young Japanese. “You would like a room,” he stated, rather than asked. “Yes”, I relied. “A cheap room.”

“I do you special offer,” he smiled, “only 12,000 yen.”

Twelve thousand yen! £38!

“I’ll take it,” I heard myself say. Meike and I were exhausted.

We awoke at about seven o’clock. Although we had snoozed a little on the plane we had had no real sleep since Wednesday night and it was now Saturday morning.

I thought of our arrival at Narita he previous day. Riot police, in visored helmets, flak jackets, long staves in hand and guns at hip, had ringed the airport. Barbed-wire hedgehogs were everywhere. “Looks like an invasion’s imminent,” I said to myself. Later I learned that the build the airport the government had forcibly dispossessed many farmers of their land and this had led to “radical groups” bombing the airport.

At about 9 o’clock we pedalled towards Tokyo. The day was overcast but extremely humid. We had not breakfasted at the hotel, and on seeing an attractive-looking coffee-house we stopped.

Up came a waitress with a glass of iced water for each of us.

The menu meant nothing to us. “Toasto to cocha, o Kudasai!” (toast and tea, please), we ordered.

The beautiful, sloe-eyed girl giggled at our Japanese. We had learned to ask for “cocha” (black tea) and not cha (insipid, tasteless green tea) even on the plane coming over.

After a couple of hours’ riding we stopped for elevenses. One complication of touring in Japan is that frequently on entering a town the road becomes elevated and cyclists are not allowed on the elevated sections. Thus one has to turn off down a slip road, find the way through the town, and pick up the road as it comes back to earth on the far side of town.

On hearing a commotion around the corner, I peered down a side road and saw a procession approaching.

Pulled by people of all ages, from tiny tots of four or five years to young adults, was a shrine on a carriage. Everyone hauled on a rope to trundle the shrine along. They were dressed in colourful costume of medieval Japan and in gay, festive mood.

One young man stood on the carriage and rhythmically thumped a huge bass drum. Hoping that they would not object to my taking photographs I approached. Far from minding, they showed good-humoured approval.

Three or four young men suddenly surrounded me, smiling and gesturing. They wanted me to don their robes and bang the drum. Wearing ceremonial jacket and headband I must have looked an odd sight, with cycling shoes and racing shorts!

We found the hostel early so we sat on a bridge over a river watching the world go by. At opening time we made our way to the hostel to be confronted with a small notice on the door saying “Youth hostel closed. New one open at Iidabashi”.

Meika in the Chiba YHA Gardens

Although Iidabashi was only three kilometres away, we had the devil of a job finding the hostel. Perhaps that was not surprising because we eventually tracked it down ~ or I should say “up” – on the 18th floor of a new skyscraper building, Central Plaza.

Wheeling our bikes across the marble hall to the lifts we felt a trifle incongruous, but up we went.

The rule in Japan is that on entering a house or restaurant one removes one’s shoes and puts on slippers provided. This we did and then explored to find air-conditioning, four beds to a room, reading lamps, lockable lockers, television and high—fi stereo equipment.

There were also loudspeakers on which the warden’s staff broadcast in Japanese and English.

After dinner — noodles and rice with chopsticks — we went out for a walk.

Our walk down darkened side streets led us to a Shinto temple, where a ceremony involving chanting and dancing was taking place in a small square fronting the temple. Young girls in geisha costume looked doll-like and beautiful.

Undressing for bed at the hostel I was given food for thought by my room—mates, an Aussie and an American.

“Did you feel the earthquake last night?” asked the Aussie.

“Sure did,” replied the American, “Quite a strong one.”

Earthquakes! Eighteen floors up! That night I slept fitfully.

Sunday morning we were up and away by 8.15.

Entering the town of Ebina we halted for a snack. Mouth-watering peaches, as large as grapefruit, reposed in little paper cups. We bought two, at 60p each.

Synthetic, computerised music suddenly assailed our ears. “Coming through the Rye”! On investigation it transpired that when the green man showed at pedestrian crossings Robert Burns got an airing, then when the red man showed the music was replaced by “Cuckoo, cuckoo”.

With Ebina about four kilometres behind us the weather changed. One moment we rode in warm sunshine! the next the skies opened. Rain bounced two-feet high off the road as we struggled for our capes. An empty garage beckoned invitingly and we paddled into its security, hoping that the owner wouldn’t drive in hastily.

Ten minutes later and all was azure. We had cycled only one mile then Meike punctured. Through Atsugi we joined Route 1, following the coast. Above the beach, which lay to our left, was a huge, concrete motorway.

On a premonition we stopped and phoned the hostel. Closed. Trimming our course slightly, we headed for Odawara, a sizeable coastal town.

Once again we encountered a friendly policeman, who directed us to the Hotel Oranjie just around the corner.

After a shower and change of clothes, we set out to explore. Soon we felt the first gnawings of hunger and, after gazing wistfully at the plastic display dishes in the Window of various restaurants, we eventually succumbed to the blandishments of Big Mac’s. Chips and eoffee and that was it. We had no money until the banks opened next morning.

Next morning it was bright and sunny and we went out for an early stroll around the town. It was colourful, attractive and clean, with all the shop fronts nestling beneath permanent sun canopies.

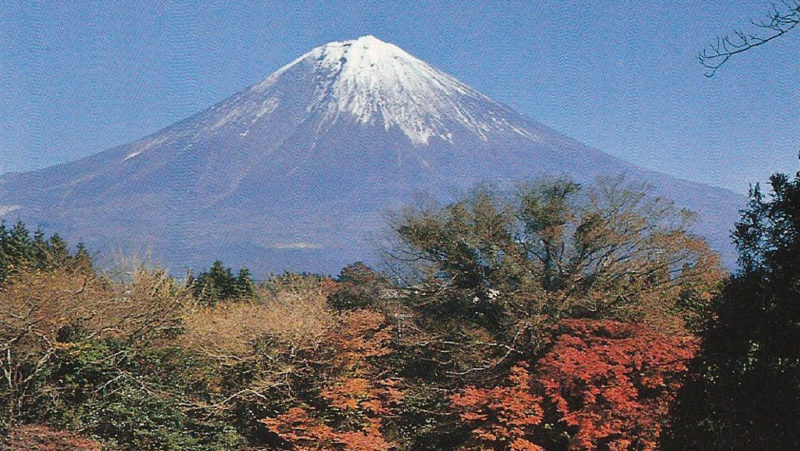

With travellers’ cheques changed at the bank, off we set ~ into the mountains. Fuji-Yoshida was our destination, about 40 miles inland, near Mount Fuji, or Fuji-san, as the Japanese call it.

Not a particularly long ride but it meant a climb of more than 3,500 ft, to reach our destination.

The road climbed fairly steeply from the town and for the first time we saw country rather than town. There were exotic shrubs and trees, some highly perfumed. Dark green foliage of the fir- clad mountains lay all around. Tea shrubs, figs, pomegranates and plums grew abundantly.

Up and up snaked the road, thrusting higher and higher into the green-clad crags. Cicadas chirmped everywhere.

Suddenly, the road petered out into a rough track. I was a little ahead of Meike and kept going, hoping it was a temporary repair stretch. On and on I climbed, sweat pouring from me. The track became narrower and rougher.

Meike caught up with me and we stood silently in the vast wilderness. No sign of habitation was to be seen. Do we go on, or do we turn back?

The silence was broken by the sound of an approaching two-stroke engine and down the track came an old man on a moped.

I sprang into his path, determined to stop him, waving my arms like a dervish. He stopped, astonished.

“Routo e Gotemba?” I asked, naming the nearest town on our route.

“Gotemba?” he paused, stroking his chin. “Gotemba!” Light dawned in his eyes. “Hai!” he pointed up the track. “Hai, Gotemba”.

Ugly as he was, I could have kissed him. Relief flooded me. On we struggled until at last the track levelled. Sounds of engines floated up from the unseen valleys below and suddenly our wheels rolled on tarmac again. Into a mountain village we crawled and into a coffee-shop.

Leaving the village we plodded on, the road always climbing, now easily, now steeply, but unrelenting upward. Eventually, we reached the top after one last hairpin bend.

Oh, the relief of descending, the cooling breeze refreshing and life giving. Upwards plodded some Japanese cycle tourists. We waved to one another, then we whistled round the next bend.

Dusk was beginning to fall as we sped past a lake with ski-ramps and sailing boats. Into Fuji-Yoshida we rode and I popped into a tyre-fitting station. The men did not know the hostel’s whereabouts but rang the number, gathered the details from the warden, and drew us a sketch-map which took us there.

It was a Japanese style hostel which meant tatami mats (woven rushes) on the bedroom floor and mattresses from built~in cupboards laid on the tatami mats making one’s bed. Sliding paper-covered doors led into the rooms and we had a room to ourselves.

The woman warden spoke little English but was pleasant and helpful. On a desk inside the front door stood a stuffed Japanese fox surrounded by books, telephone, and various impedimenta.

Up a steep, creaking, wooden staircase we went, saddle-bags tucked under arms. No handrails and highly polished treads seemed a recipe for trouble.

After settling in we met Ethel. Ethel was Irish, and hostelling in Japan by rail. She had the freckled, pinkish skin of so many Celts and a friendly, open face.

“Are you coming to the bath-house?” she asked, after introductions. She explained that as there was no hot water at the hostel, we were entitled to a free ticket to the local communal bath-house each day.

On reaching the bath-house we were confronted by a woman sitting in a kiosk. She took our tickets and in we went, women entering through the left door, men through the right. These doors led into changing-rooms, both of which the woman could clearly see from her vantage point.

Undressing in company with a couple of Japanese I glanced around. On one wall hung a huge mirror, perhaps 8ft long by 4ft high. From the changing-room a sliding glass door led to the bathroom, a room measuring about 20ft square.

The Japanese each squatted on a tiny plastic stool near a series of low taps on the wall, once again mirror lined. Producing huge flannels they proceeded to spend about five minutes impregnating the flannel with soap before beginning the ritual washing. Every nook and cranny was washed, rewashed, and washed yet again.

They spent 20 minutes simply bathing, rinsing, lathering, rinsing. I spent five minutes or so. Only when scrupulously clean does one enter the bath itself.

The two baths were each about 10ft by 8ft by 3ft deep and extremely hot, steam hanging above them. Gingerly I dipped a tentative hand in. “Bloody hell,” I said. The thermometer registered 43 degrees Centigrade. After a couple of minutes I forced myself in.

Sweat poured off me and soon I scrambled out again. As we dressed I noticed the the huge mirror was well used by the locals to admire themselves — I even caught myself doing it!

After an hour’s chat with Meike and Ethel at the hostel we turned in.

One moment I was sleeping soundly, the next wide awake. “Curious,” I thought, “why have I woken?“ The answer came immediately — a quite violent rocking of the building. Once again it shuddered, then all was still. Our first earthquake!

While at breakfast next morning in a baker’s we had been invaded by a band of Japanese young men in ceremonial dress with one wearing a hideous head mask. Some played flutes. others chanted while “Shushi”, as the masked character was called, performed a dance. This was evidently some sort of ceremony connected with a festival at the temple and the band roamed the streets all day, visiting shops, cafes, and restaurants at random.

The girls having returned from bathing we decided to visit the carnival at the Shinto temple, and off we set. Dozens of stalls and great throngs of people met us there. Octopus and squid were being fried, riceballs prepared, eels were swimming in tanks, as were baby turtles. All manner of strange delicacies were on sale — I bought a toffee—apple!

Becoming sated with the festival, wondrous though it was, Meike and I wandered off into the back streets in search of a Japanese pub.

Eventually we peered into a cafe—restaurant type of place and a woman smiled a welcome so in we went, even though it seemed closed. The owner and two or three friends were drinking at the bar and watching Sumo wrestling on television.

We seated ourselves cross-legged at the low table and ordered an orange juice and a Sapporo beer.

The bar party tried to chat to us but conversation was desultory until one man approached with a bottle of Suntory Japanese whisky and a glass. Pouring a huge shot into the glass he handed it to me. “Japanese whisky, you taste,” he smiled.

I took the glass and sipped cautiously. “Umm”, I said, “very nice.” To my palate it was indistinguishable from Scotch. I drained the glass and the Japanese applauded.

Each morning at Fuji-Yoshida at about seven o’clock we heard the temple bells, unlike any bells I have ever heard. Ethereal, delicate, liquid notes as though the bells fashioned of purest crystal floated gently through the still mountain air.

Ethel invited me into her bedroom to see Mount Fuji from the balcony, and there it was, the sacred mountain of Japan, veiled in white clouds.

Ethel left for Tokyo that morning and Meike and I decided to have a gentle potter on the bikes to Kawaguchiko and Saiko, two lakes only a couple of miles apart.

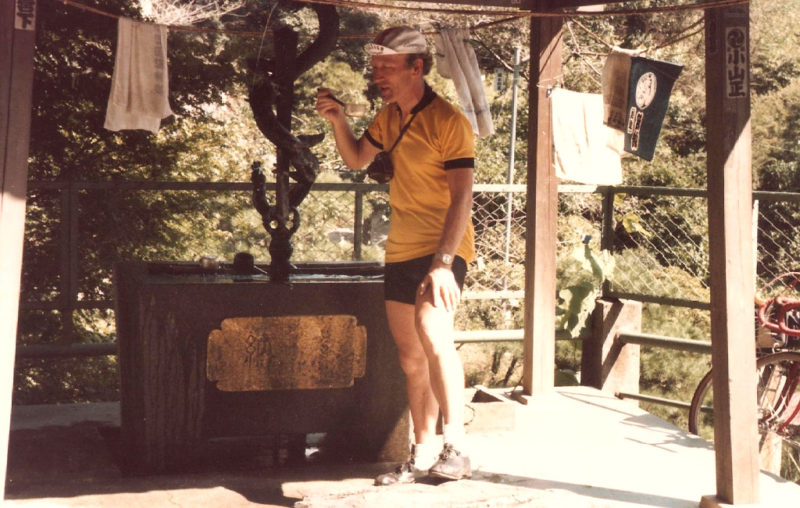

John with silent policeman towards Lake Saiko

Next morning. we lay cosily in bed waiting for the glorious temple bells. Today we were going up Fuji-san. A good map, borrowed from the warden, showed contour lines, paths and other details.

Access to the fifth stage, height just over 7,500 ft, could be had via a serpentine road. The mountain lay about 25 miles from the hostel and it meant 4,500 ft of climbing to reach the fifth stage.

Meike chose to take a bus up and meet me there.

Soon I reached my turn-off point from the main road and on to the road to Fuji—san. It was fairly narrow. but beautifully surfaced — and it was a toll road!

I stopped to take pictures, then settled to the climb. The road initially was quite straight, with shrubs and trees in profusion on both sides. Quickly I found myself down the gears and beginning to puff. Unused to climbs longer than those of the Surrey hills I was trying to climb too quickly. I reached bottom gear (34 inches) and still it was hard. Then the gradient eased and I snicked into 43 inches.

Kilometre posts lay on my left, giving height, and I was able to watch my climb with great precision.

After an hour’s climbing from the start of the toll road I had covered 16 kilometres and reached stage two, with a lay-by and toilets.

Soon after that I rode‘into thick mist which worried me, for although traffic was light drivers would not expected a cyclist here. I didn’t see another all the time I was on the mountain.

Now the straights were short and the bends tighter. As I climbed still higher there was a pronounced drop in temperature. It had been warm at Fuji-Yoshida but now it was quite cold.

To my relief the mist abruptly broke to give clear air. On looking to my right I saw that I had climbed through a cloud-base which now lay like cotton wool below me, pierced here and there by lesser mountain peaks.

Hairpin now followed hairpin as the beautifully engineered road wrythed ever upward. The wind was now gusting strongly and for the last mile or so the gradient reared viciously. The 32nd kilometre post came into View and I had reached the fifth stage, height 2,305 metres. The 32 kilometres of toll road had taken me two hours of riding time.

Meike was already there, having seen me from her bus window earlier. After a couple of photographs we found a restaurant—cum-souvenir shop.

A sudden tattoo on the window make us look up. Rain was falling heavily and the outlook was bleak. I waited for the rain to ease.

Eventually, it did ease and, caped up, I started the descent. It was disappointing to have wet roads as I had been looking forward to a fast freewheel down 32 kilometres of glorious bends. Cautiously I applied the brakes, feeling the wind tearing at my cape. With cape, tracksuit, and peaked racing hat on I felt snug most of the time.

Some of the bends were deceptively tight and made me suck my breath as I was forced to lean over further than I wanted in order to get round them, but eventually the road straightened and it became warm again.

With somewhat sad hearts we bade farewell to Fuji-Yoshida. It had been a lovely place to spend a few days and we felt that nowhere else would match it.

We heard the temple bells for the last time and then we set off. The ride was easy, being virtually a 40-mile freewheel through glorious mountain scenery.

Drink in gardens of restaurant up mountain pass to Sagamiko

On reaching our destination, Sagamiko, we found ourselves crossing a modern suspension bridge and seemingly heading back into the mountains. Across the road was a group of motorcyclists so I approached them for directions. None of them knew the hostel’s whereabouts but one kicked his bike into life and sped into town. Ten minutes later he returned and pointed to a building across the bridge on a hill. That was the hostel!

Our fears were realised. After Fuji-Yoshida, Sagamiko was a letdown. The hostel was a purpose—built concrete building with little to commend it. We booked in with a young man and then had a shower.

Sagamiko hostel & warden

Our money was dwindling fast so next morning we headed for the nearby town of Hachioji, which boasted a Tokai bank, the only place, it seemed, that would give us cash against our Mastercard.

Although Hachioji was only 12 miles away there was a mountain pass to climb to reach it. Off we set on a lovely sunny day, up the pass.

Once over the top of the pass it was an exhilarating freewheel in the sunshine down to Hachioji. On enquiring of a smart traffic policeman, complete with white gloves and whistle, we learned where the bank lay.

Meandering back up the mountain to Sagamiko we were passed by a couple of racing men, complete with white dome helmets. Each rode a track bike, fixed heel, gear of about 80 inches and each had one brake — on the back wheel!

Sunday dawned sunny and warm and off we set, back up the pass, heading for Kamakitako. The Kamikaze squad were out in force, four and six-cylinder engines screaming like demented banshees down the mountain road. Debris on one or two bends indicated a coming to grief of the odd racer and, indeed, rounding the next bend we saw a young lad ruefully surveying a badly bent pair of front forks on his Yamaha.

I was surprised to see that although. in general, the Japanese were safetyv conscious, they allowed little children to stand on the front seats of cars. Drivers frequently were not wearing seat belts and a few mothers drove with infants in papoose—type harness on the mother’s back.

On we cycled, through Hanno and reached a place called Hidaka. A pituresque shrine by the roadside, with incense burning and lighted candles, caught our eye. Opposite was a beautiful drinking-fountain, most ornate, with serpents spurting water and a thatched roof.

Drinking fountain at roadside shrine, Hidaka

At that moment a Japanese cyclist came into view and stopped at the fountain. He was, I guessed, about 40 and looked fit.

Seizing my chance I asked him for directions to Morro. near which lay our destination. He spoke some English and said he would guide us to Morro.

Off we set, congratulating. ourselves on our good fortune, for finding one‘s way was difficult with the maps we had. After a while he stopped to ask directions of a villager.

The villager pointed in the direction from which we had just come. My heart sank. Our guide disputed this at great length with the villager and then we turned left along a country lane. From the sun I could see that we were travelling in constantly changing directions. At a level crossing I whispered to Meike. “Let‘s lose him. He’s got less idea than we have where we are.”

Again our good Samaritan stopped to enquire the way and we slipped away. We pedalled furiously for a couple of miles, fearfully glancing back from time to time, but he wasn‘t following.

Rice drying a Kamakitako

Fairly soon we were on the lane to the hostel at Kamakitako. The lane climbed through a broad, sun-drenched valley with mountains each side and the delicate green of paddy fields showing vividly against the dark, fir-clad foothills. Up went the road until we came out to a lake, obviously a popular resort judging by the throng around it.

The hostel lay almost at the water’s edge and once again it was a concrete, two-storey, barrack-like structure. Meike was called to the phone while I showered. It was our Samaritan guide, enquiring whether we had arrived safely. We did feel guilty at having given him the slip and were rather touched at his soiicitude.

We had planned a trip by train to Kawagoe the next day, in town about 25 miles away which had some medieval houses and a castle which, we were told were well worth seeing.

The day was hot and the town not very interesting. Though we did see and photograph the houses and castle, the journey hardly seemed worth the effort.

Tuesday morning we left Kamakitako, bound for Tokyo. 1 was not relishing the ride as it was really cross-country and I feared for our ever finding the way.

By sheer good luck we sailed along, never losing our way once. At one busy place nee we found a junction with directions in English – oh, bliss!

Riding through a village we spotted a croquet match — not on lawn but on sand.

Soon we were invited to take tea with the players, which we did. Then on to Tokorozawa, our lunch destination. After cakes and iced coffee at a friendly baker’s. we came on to a Kingston By—pass type of road with heavy traffic all the way into Tokyo.

Meike outside bakers at Tokorozawa

The women in Tokyo were in general much more stylish than the provincials and frequently attractive. Their hair, usually fairly short, with a bluey—back deep sheen, looked rich and healthy. Kimonos were commonplace.

We booked into the hostel for three nights and I met my room mate, a tall, slim New Zealander with long, blond hair down past his shoulder blades. About 22 years old, he seemed somewhat ingenuous in the ways of the world. He showed me proudly a box of “magic” tricks that he had bought that day, the star item being four steel rings, each about four inches in diameter which, he claimed, could be linked to form a chain if struck hard together in a certain manner.

When I left the room he was sitting at the table. striking the rings one against the other and muttering: “I’ll get the hang of it. All it needs is practice.”

Wednesday morning after breakfast Meike and I walked from the hostel and to the Tokyo Imperial Gardens wherein lay the Emperor’s Palace. The gardens were well kept and attractive, with many exotic species of trees and shrubs.

Leaving the park we walked in bright sunshine along a broad avenue flanked by a river on our right. Along the pavement was painted a white line and cyclists used the half nearer the road, the other half being for pedestrians. The system seemed to work well.

Our walk led us to British Airways’ offices as we wished to enquire about our return flight. We particularly wanted a Saturday flight, which did not seem available.

“Well. you can go along to Narita if you wish. There may be a cancellation or two,” we were told. We departed and headed for the Ginza, the Bond Street of Tokyo, not far away. Along the Ginza we strolled, window shopping as we went. Large, tasteful department stores lined the Avenue.

A subway train took us to Shinjuku, the Soho of Tokyo. Extremely colourful were the alleys and streets, with dozens of touts on the pavements.

Next morning we went to a street market area of Tokyo called Asakusa. There were miles of arcades and markets and another lovely day — but no bargains.

We then decided to take a trip on the river and set about finding the jetty. While Meike popped into a toilet I wandered idly along when suddenly half a dozen kimono-clad women went by. The last one, a dainty little girl, by my side, smiled, and spoke in Japanese. Ingratiatingly I smiled back. “Eigo o hanashimasu ka” (do you speak English?) I asked, hopefully.

She giggled and started to say “Leetie English” when Meike re-appeared, just in time to save me from a fate worse than death.

Tokyo Central Plaza

Tokyo, as a city, had been disappointing, therefore we were not sorry to be heading eastward towards Chiba youth hostel, about 40 miles distant. With a tail wind we made good time, noting that in the morning rush hour nearly every major junction had a policeman keeping sharp scrutiny for malefactors.

Many pedestrian crossings had bins attached to posts on the pavement on both sides of the road. In the bins were yellow flags with Japanese wording which, I was told, read “I wish to cross the road.” Schoolchildren took a flag from the bin, held it up for motorists to see, marched across and dropped the flag in the other bin.

Nearing our destination I went into a motor-cycle shop to enquire the way, the manager reacting in disbelief when I replied that we had come from Tokyo that morning.

“Oh look,” called Meike as we rode along. “Cows!”

Cows they were, the first we had seen in Japan. We never saw a sheep.

Past a huge radar tower we rode, catching the first farmyard smells of our stay from the underlying farm, then we turned left up a private drive to the hostel.

A two-storey dark brick building surrounded by pine forest and with a “cricket pitch” type of field adjacent to it, it was brand new, having been opened only weeks before.

“When are you leaving?” was the first, less than welcoming, question.

“Tomorrow,” I replied.

“Ah so, but what time?” persisted the warden. I answered, “Eight thirty—nine.”

Studiously he entered this important piece of information on the registration form.

All the floors in this aesthetically pleasing hostel were tiled with beautiful mosaic patterns and the walls were finished in a dazzling snowy white stipple.

Following the ritual bath — just the two of us — we entered the dining room for dinner at seven o’clock. Four Japanese, all middle-aged and certainly from their dress not hostellers, were our sole companions.

Leaving Chiba hostel late — 8.45 instead of the estimated 8.39 — after a pleasant breakfast, we wended our unhurried way along country lanes in the direction of Narita Airport.

The earth was a fine dark brown soil and we noted another, to us, new crop — peanuts. Maize and corn-on-the—cob grew tall, and low tea bushes abounded. Harvested rice lay in bundles over wooden trestles to dry in the sun, and the occasional farmer, with coolie hat on, toiled in the fields.

On reaching a small town called Yachimota we stopped for a browse and elevenses. Climbing back on to our bikes we continued on to Narita City, finding it pleasant and thronged with people along its narrow, winding main street.

After a light lunch we left our bikes locked together and wandered around the town, then bearing in mind the British Airways forecast of a full plane, we decided to head for the airport, about five or six miles away.

Finally: “Sorry, flight full. Definitely no room.”

A security man said that we could kip down in the airport for the night. We had to check our bikes into left luggage (1300 yen) and during a most uncomfortable night we were visited twice by security patrols, woken, had our passports and tickets checked, and made to sign forms giving various details.

Only one flight in day to London! What if tonight‘s were full? Money was low. Did Japanese for Travellers include the phrase: “Where is the British consulate?” I wondered.

We decided to return to Narita City and hopped on a bus. Although still early, the day was already hot.

A stroll down the winding high street led us to a Buddhist temple, and what a magnificent building! The main temple was a five-storeyed pagoda ornately carved, lacquered and varnished. The colours were vivid and startling in their intensity. The golden dragons’ heads, dozens of them, were fearsome to behold. Hideous gargoyles grimaced and snarled wherever one looked.

Exploring further we found a lovely ornamental park within which were two lakes, at different levels. The park contained beautifully scented shrubs, swans, turtles, golden carp, pergolas, and bamboo-like trees.

Time was passing and we took a bus back to the airport.

The Sunday plane had plenty of room and as the 747 gathered speed along the dark runway, the runway lights flashing past the porthole windows, I had mixed feelings. It was good to be going home but sad to be leaving such a beautiful country.

TECHNICAL NOTES

My bike, the Leader, was equipped with Weinmann 27in hp rims with Campag Tipo hubs, and 14/16 butted rustless spokes. Stronglight 49D’ cranks with single TA ring. Gear: Sun Tour Cyclone. Block: Sun Tour Ultra Six. Chain: Sedis. Ratios (38 tooth chaining, 13, 15, 17, 20, 24, 30 sprockets): 79, 68, 60, 51, 42, 34 inches. Tyres: Nutrak Nomad. Sad- dle: Brooks B17N. Saddlebag: Karri- mor Silvaguard. Brakes: GB Coureur. Mudguards: Bluemels Sovereign. Carrier: Tonard steel. ,

The Sun Tour Cyclone gear was the standard short-arm version yet was capable of handling the 30-tooth sprocket with absolute certainty every time. The makers, I think, state its maximum capacity as 26 teeth!

Meike’s bike, the Emperor, had slightly lower gears, using a 36-tooth ring.

JOHN TURNBULL