Turnbull Tours: The Galibier

.

The not-so-gentle giant

I took my bike to the Alps for a 10-day jaunt in the mountains in August. During that time I covered over 600 miles to achieve a life-long ambition — to climb some of the highest passes in Europe.

The bike, an Allin, built for me in Croydon in 1963, has served as a club-run bike, a racing bike, and a touring bike. On tour it ran like clockwork, not even one puncture marring its progress.

The British Caledonian One-11 pilot throttled the engines back to a mere whisper and we began the silent glide down from 29,000 feet to Geneva airport. Only an hour ago I had left Gatwick after detaching the pedals and turning the bars of my 23-year-old Allin, and seeing it loaded on to a trolley by baggage staff. No charge for the bike; it travels as luggage.

Geneva airport appeared friendly, as airports go. It was small, and seemingly lacking the high-profile security of many of the larger airports. Pedals restored and bars straightened, saddlebag fitted, the Allin and I wended our way cautiously into the bright sunshine within half an hour of landing.

For many years I had nurtured a desire to ride over the Alps, a desire heightened by recent television coverage of the Tour de France. Had I left it too late at 52? I didn’t know.

Heading south I came to the French border after only seven or so miles. A glance, a smile (my club’s colours are very maillot jaune), and the customs officer waved me through.

Having no definite plans I had decided to see how I went, using youth hostels, gites, and cheap hotels as convenient.

More than once I was disconcerted in Switzerland by my road suddenly changing to a motorway with no alternative apparent; nor was it marked as a motorway on my recent Michelin 1:200,000 (roughly three miles to an inch) map.

Annecy hostel being full, I rode on past the picturesque lake to Faverge, and on enquiring at the tourist office I was told that a bed could be had at a gite seven kilometres back. Back I went, then up a steep lane off the main road to a delightful mountain village, Amand Doussard. There were tubs of flowers everywhere. and the delightful (to my nostrils) aromas of the farmyard pervaded the atmosphere.

Soon I found my gite, a traditional Alpine chalet. A smiling girl greeted me. “Yes, we have a bed, if you don‘t mind sharing a room with three girls.” At £3 for the night, it appeared tempting. I shared!

Pont du Calle, near Annecy

Next morning saw my biggest day’s mileage, 75, more than I had intended. The Galibier drew me to it, as though by some inexplicable force. My imagination and memory of reading of the exploits of Coppi, Bartali, Kubler, Koblet, Bobet and Anquetil made it a must. At almost 9,000 feet stood the giant. I shivered at the thought.

The day was hot as I wended my way through Albertville, then through a long, rocky gorge to my intended stopping place, St Maurice de Maurienne.

On the map it looked idyllic. In reality it was a town with large factories straddling the river banks, and I quickly decided to turn off and head for the Galibier. The climb out of town was frighteningly difficult with the road rising in steep serpentine loops and the sun burning down. Within seconds I was in bottom gear (35 inches) and creeping. In my enthusiasm I had overlooked the fact that the Col du Télégraphe stood between me and the Galibier, and at around 6,000 feet was in itself no mean climb.

Lower reaches of Col du Télégraphe

Sweat trickled from my cap in a constant stream, and every five or six kilometres I had to stop to rest and drink. On restarting, the going seemed easy, but within a kilometre it reverted to a painful plod. After a fruitless diversion up five kilometres of dead-end track in search of a gite which, it transpired, had no spare bed, I resumed my plod up the Télégraphe. The utter relief at reaching the summit and then dropping like a stone to the mountain ski resort of Valloire was indescribable. The town appeared “en féte”, with pennants flying everywhere, people basking in the bright sunshine and sitting beneath huge, splendid parasols while sipping ice-cold drinks.

Lying on my hotel room bed I thought to myself: “This is how Robert Millar probably felt”. My chest and stomach ached, my right knee felt painful and my ankles ached. My heart thumped like a diesel engine. It had been about 20 kilometres of really fierce climbing. Tomorrow the Galibier loomed large and steep. Apprehension gripped me. “Have I bitten off more than I can chew?” ran through my mind. I had very serious doubts of my ability to continue.

Amazingly, next morning I felt completely normal. My confidence returned with a good, leisurely breakfast and with full water bottle off I set.

Gently wending my way upwards through pine forest at first, I felt invigorated by the beautiful scent and grateful for the cool shade. On leaving the tree line behind I quickly felt the sun’s heat, the intensity of which appeared to be amplified by reflection from the rocky mountainside.

Plenty of cyclists were in evidence, mainly in the form of bikes on car roof racks. It seemed a popular tactic to take the bike to within 10 or 15 kilometres of the top by car, then set off for the summit on a stripped-down racing iron with the wife or girlfriend following in support with refreshments.

The higher the road climbed the steeper it became, with tortuous hairpins more and more frequent. I looked up vertically and saw traffic above my head, hundreds of feet higher. My heart sank; the way up seemed virtually impossible by simple human leg power.

Near the summit

Painfully I levered myself higher and yet higher, the road becoming much narrower now and less well surfaced.

I had caught a fellow rider, an elderly German, with wife driving a caravanette in support. “How old are you?” he asked in German. I told him. “I am 57”, he replied, with some pride.

Pelts drying in the sun

Just before the summit was an excuse to stop – a mini market of stalls with animal hides stretched out in the sun, waiting for buyers. While I took a few photos my German friend crawled past. I gave him a wave and a smile. Remounting, I continued up what I judged to be a one-in-six gradient and three hairpins later there was the top! The exhilaration was almost overwhelming. The views were superb, with jagged, snow-capped peaks surrounding and brilliant blue sky. Plenty of people, both motorists and cyclists, were milling around, but no cafés, restaurants, or trinket shops.

My first reaction was disappointment. No postcards franked “Col du Galibier” could I send. Then my mood changed. No, this is how it should be. Merely a narrow mountain road, simply a plaque marking the height, in the mid of what could obviously be a savage, dangerous, wilderness, given inclement weather.

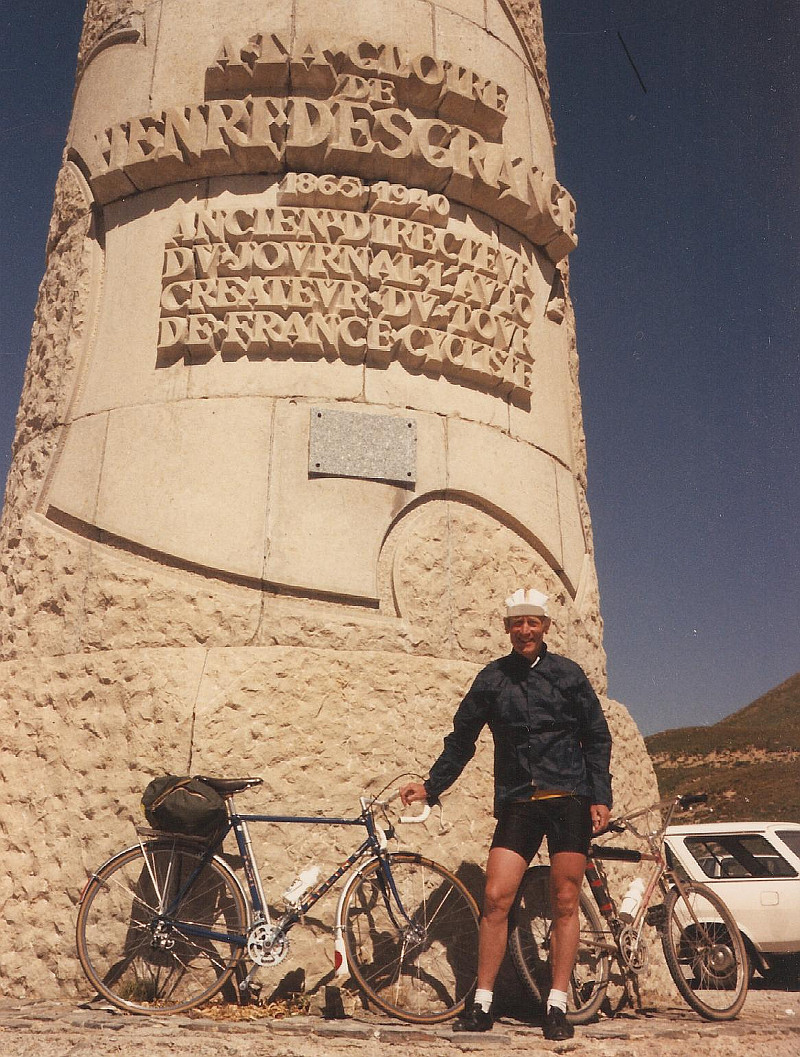

The view from the top. Henri Desgranges monument is bottom right

The monument itself

After drinking in the intoxicating views and taking more photos I donned a plastic racing cape for the descent, which looked frighteningly steep. One hairpin bend down I stopped to look at the monument to Henri Desgranges, the founder of the Tour de France. Mentally I doffed my cap to the riders who race up these cols for a living. The suffering must be unimaginable, the deadly combination of distance, gradient, and heat grinding down even the staunchest of men. Climbs of 40-odd kilometres were, until then, an unknown world to me.

The last 17 kilometres to the top had taken me two hours, which is about five miles per hour. “Enough of mountains”, I thought, “head for flatter ground”. On the way down I passed a cyclist pushing his bike so I slowed to see if he needed help. He did — a Frenchman — he had punctured, changed a tub, but had no pump. A dangerous omission out here, I thought, as I watched him use mine.

Start of a 25 mile descent

The Col du Lautaret appeared to stand in my way but to my relief it was all part of the gigantic freewheel for hours until I reached Bourg d’Oisans, a town at the foot of Alpe-d’Huez. I wasn’t tempted to climb that, but found a gite near the town centre and collapsed into an invigorating shower.

My bedside companion in this gite was a tall, slim, blonde, French girl of about 18 who in the heat wore very little to bed and didn’t cover herself either. Because of the noise of a fairground nearby I didn’t fall asleep immediately and was very conscious of this very attractive girl lying within arm’s-length. I suppose I should mention that her parents were in the same room as well!

Next morning I headed for Grenoble, mainly downhill through rocky gorges, and via a pleasant town, Uriage. Grenoble was a great disappointment, though surrounded by snow-capped mountains, and I quickly threaded my way out and headed north.

Learning that French beer came in tiny glasses and was relatively expensive as a thirst quencher, I had taken to buying a litre carton of chilled milk at a laiterie or crémerie for about 40p and a couple of cakes or packet of biscuits from the boulangerie for elevenses. This, I thought, was delicious and good value.

I stopped at Touvet after a hot ride. On the way I had seen a sign advertising fruit for sale at the roadside so had pulled in under the shade of a large tree to find a girl selling huge peaches and nectarines. Choosing one of each, I was amazed when in reply to my asking how much they were she replied, “nothing”, and gave them to me. Perhaps she simply felt sorry for me.

On my way I had seen hang-gliders flitting about at the edge of precipitous mountains, then ordinary gliders, six in number, circling in close formation, trying to gain height above a small aerodrome.

Leaving Touvet after a snack I headed for Chambéry where I found a hotel room for £5. Not the Ritz, but good enough for me for the night. That day’s ride was 70 miles. In the evening, after a stroll around the town, which had many attractive mediaeval features, I feasted myself on chicken, salad, wine, peach melba and milk.

Chambrey public gardens – early start

My morale had risen again and I resolved to return to the mountains on the morrow — I wanted to ride up the Grand St Bernard pass. Accordingly I took the road to Montmélian, then a beautiful route through miles of vineyards. Back on the main road again and two cyclists waved me down. They were French boys, about 17, and asked me whether they were on the right road to Grenoble. They hadn’t a clue where they were and seemed surprised that I not only had a map but also knew our position. Ruefully taking my advice, they turned back whence they had come, for their road lay about six miles away.

The road started climbing steadily now, and the sun was hot, really hot. Luke-warm water in my bottle was better than none at all, but it was with relief that I rode up the steep road into Flumet and spied a drinking fountain under the shade of a large, open-sided roof. How pleasant it was to sit on the edge of the fountain, drinking ice-cold water, and be shielded from the sun. Up rode a cyclist on a racing bike to join me. He had a Manchester Wheelers shirt on and was staying in the area with his wife. I envied him his unencumbered bike.

Flumet: hard hot climb to delicious icy water

Reluctantly I restarted, heading for Mégeve, and still climbing. From there the road dropped dramatically to St Gervais Les Bains, my destination for the day. I loved the exhilaration of the fast descents on smoothly surfaced roads, but hated the thought of the height lost which would have to be regained.

The Allin loved the fast descents, never twitching or hesitating, always rock steady and responsive, whether on the 50mph straights or heeled over into the bends.

Towards Mégeve

My accommodation turned out to be a gite, about two miles out of town up a steep hill. This was a superior one, with a room to myself, and very clean. After showering and changing I went into town and had a very tasty dish for dinner, spaghetti carbonara. A feeling of euphoria enveloped me. I could climb any col!

Breakfast next morning in the gite produced a shock — it was raining. By the time I got on the road it had almost stopped and my route began with a climb up a viaduct about three kilometres long. The road continued to climb into the mountains and led me through Chamonix. The views of snowy peaks were superb, but the town was so commercialised that I rode quickly through it, stopping for lunch at a delightful mountain town of Argentiére. There was a kermesse, or fair, in progress, with lots of stalls, games, competitions and snacks evident. I sat in the sun on a comfortable bench, eating, drinking, and watching the world go by. Delightfully relaxing.

Long climb up viaduct out of St Gervais

Shortly after, I arrived at the Swiss border and changed all my French money for just two Swiss banknotes. It didn’t seem very much in my wallet. The road continued to rise but now more steeply and then cruelly. This was the Col du Forclaz, only 5,000-odd feet. but a nasty one. Gaining the top I then bulleted down at frightening speed to Martigny.

The road was skilfully engineered to drop down almost a sheer precipice with many very tight hairpin bends, which meant running down the straights at about 50mph and braking to 10mph for the bends. My ears popped with the loss of altitude and thankfully I found flat roads again.

Spotting two motorcycle policemen in an open-air café I asked for directions to the Route du Lévant, where the youth hostel was. One of them pointed to the street name-plate across the way. I was in the very road.

The hostel was difficult to find — I rode straight past it, then returned and finally tracked it down. It was completely underground, with a concrete ramp leading into it. The doors were of steel, about eight inches thick, and the walls of reinforced concrete.

“A civil defence centre”, the warden answered, on my asking him what sort of building it was. It appeared to me to be a nuclear bomb-proof shelter for local bigwigs and I mused to myself on the hostellers’ rights of tenancy in the event of an emergency and the dignitaries’ pouring in. Would a youth hostel booking take priority for a bed? I thought not.

The world’s most forbidding youth hostel

Martigny was not very interesting, though it had a castle, and a hotel that everybody who had been anybody had stayed at, including Byron, Goethe, Rousseau and Napoleon.

I had determined to climb the Grand St Bernard next day without the hindrance of my saddlebag, which would stay at the hostel. On checking the map it appeared to be a climb from Martigny of 6,500 feet in 45 kilometres.

The morning was cool and fresh as I set off at eight o’clock for the Grand St Bernard, without breakfast. Rising quite gently, the road meandered up the valley following the river, the water of which was rock-grey and fast flowing.

Kilometres flew by fairly easily and I decided I would do an hour or so and then stop for breakfast. I passed a cyclist, heavily laden, who stopped to take photos. Now the road started to steepen and I changed on to the little chain-ring. The day was clear-blue, the sun beginning to warm the valley, and the wild mountain flowers were a beautiful splash of colour.

Seeing a village ahead, and having ridden for an hour and a quarter I stopped at a little café. Rive Haute was the village, and I had done 24 kilometres already. “Over halfway”, I thought gleefully, “and not so hard.”

Sitting at an outside table in the warm sun I thoroughly enjoyed the warm crusty bread, the butter, the jam and the piping-hot coffee.

My gaze swept through a wonderful panorama of mountain peaks, their bases clad with fir forests, their upper reaches bare rock tipped with sparkling snow. “This calls for another coffee”, I thought.

“Only 21 kilometres to go,” I told my Allin, waiting patiently in the shade where I had parked him. Away we went, heading upward, always upward.

The gradient became steeper and the temperature dropped as I climbed. I didn’t mind that, as I hated sweat dripping off me in the heat. On my right appeared a dam and large lake. I rode on into a tunnel, very dimly lit, and found the reverberation of motor traffic quite unnerving. After what seemed like ages I emerged into sunshine again, the tunnel being about four kilometres long.

Stopping to check my map, I found myself about 10 kilometres from the summit. From experience I knew that the final 10 kilometres are the real killers, with gradients of one-in-six or so. Pacing myself carefully into a rising head-wind I was surprised to round a bend and see an elderly man, in long trousers, on a low-geared racing bike ahead of me. “Bonjour”, I called as I passed. “There is a wind”, he rejoined, in French. With that he stopped, dismounted, and started to walk up.

The climb became so severe that I found myself stopping every kilometre or so for a drink and a breather. The wind was now quite cold and I quickly shivered whenever I stopped.

5 km tunnel has light at the end. Frightening ride through

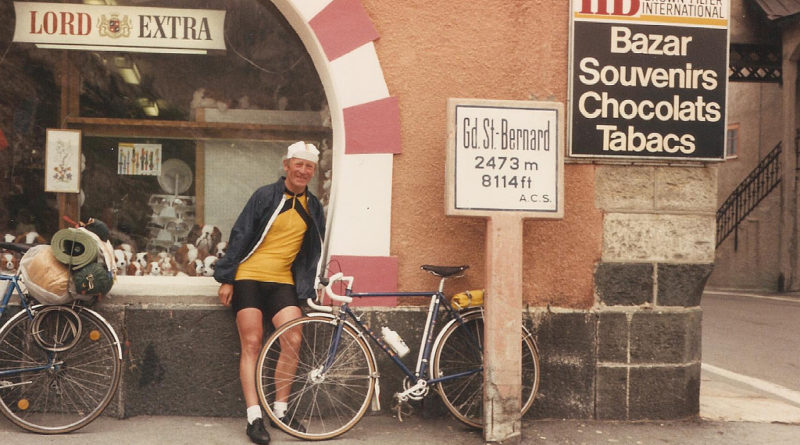

Eventually a stone building came into sight — the top at last. Over 8,000 feet above sea level. There was the hospice and monastery, all very commercialised since my visit 28 years ago. Into a restaurant, where I tucked into spaghetti bolognaise to refuel myself. Then a look at the chapel and museum, a few photos, and I donned my racing cape for the descent.

Made it!

On my way down I heard thunder and, glancing back, saw storm clouds over the St Bernard. Then rain reached me and I was pleased that I had also brought my large cape. It was quite cosy freewheeling down in my cape but the rain soon ceased and eventually I was back in Martigny, glowing with satisfaction.

Next morning I headed north on flat roads for Lausanne, passing through Montreux en route. Montreux, on the edge of Lac Léman, I thought very ordinary. Lausanne had a pleasant youth hostel, with meals provided, a godsend in such an expensive country as Switzerland.

Strolling through a park at the lake edge in the evening I saw two young men playing chess on a chess “board” of about six yards square, with pieces 18 inches high. The “board” was painted on a tarmac square and the pieces were moved by sliding them with the foot.

Following the north edge of Lac Léman, I headed for Geneva the following day, but quickly forsook the main road for the older roads of the “route vignoble” or road of the vineyards. Though hilly, it was beautiful, row upon row of carefully cultivated vines, as far as the eye could see.

Stopping at the small town of Aubonne, I refilled my drinking bottle from the perpetually flowing fountain and bought some luscious fruit at a market stall. The flower-bedecked fountains fascinated me, looking at once both beautiful and cool.

On to Geneva, and to the youth hostel which was most uninviting, with notices everywhere: “Beware of pickpockets”, “Beware of thieves”. Geneva lies at the head of the lake, and there was a colourful flotilla of boats in the harbour, with a leafy park hard by. The famous jet of water, about 200 feet high, rises vertically from the harbour mouth, and the whole panorama was lively and exciting.

In the evening I strolled into town accompanied by Volker, a young German who had attached himself to me. He was from West Berlin and had stayed with an English family in Oxted Surrey, some years earlier, and seemed very pro-English.

We dined outside the restaurant in a concourse of a dozen different tongues, a diverse, cosmopolitan company most pleasantly relaxing and interesting.

The Geneva youth hostel warden had a way of making you move. Piped music woke you gently at seven o’clock, then by degrees the music became more and more clangorous, until an hour later it was almost unbearable.

My plane home left at 5pm so I had time to wander around the old town, which was very attractive, and take photos. Next I stumbled fortuitously on a magnificent white building, with six onion-shaped golden domes surmounting it. It was a Russian Orthodox church, and I peeped through the open doors and saw that a service was in progress. To my surprise the priest was using Latin, not Russian. A few middle-aged people formed the congregation, standing facing the priest. I found it a solemn and quite moving experience.

As I had a little money to spare I decided to treat myself and was soon sitting under a parasol in a fashionable avenue tucking into a huge peach melba. Expensive, but delicious.

Then back to the lakeside for a last look at the vista of beautiful blue water backed by distant mountains. For a while I watched some water skiers, then it was time to head for the airport. The Allin was popped into a huge plastic bag, completely intact, and soon I was high above Geneva, heading homeward. Settling down in my seat I felt a sense of satisfaction. I had started this holiday with grave doubts in my mind of my ability to ride over the Alps. During the tour these doubts were reinforced when the going became really hard, but now I could relax. I had done it.

Geneva: the end of the road

TECHNICAL DETAILS

Frame: Allin 72° parallel, 531 db.

Chainset: Stronglight “99″, 42 and 30 teeth.

Freewheel: Maillard 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 23.

Gears: From 76 to 35 inches.

Gear mechanisms: Suntour Superbe racing.

Tyres: Michelin Bib Sport.

Wheels: Campag Tipo large flange on Mavic E2 700C spoked 36/36, 14/16 gauge.

Brakes: Weinmann 500.

Mudguards: Bluemels Olympic.

Chain: Sedisport.

Saddle: Brooks B17N.

Carrier: Blackburn Fastrak.

Saddlebag: Karrimor.