Part 1: Preparation & Setting Off

“You know you are in bear country? Are you carrying Bear Spray?” asks a man as he leans out of his pick-up truck on a remote dirt road in Montana. We confirmed we had Bear Spray and he went on to say, with a poker face, “You know the most effective Bear Spray manufactures? …. They are the likes of; Winchester, Colt and Smith & Western!” and then chuckled at his joke. This summed up two of the re-occurring themes of cycling across America along the Continental Divide; Bears & Guns!

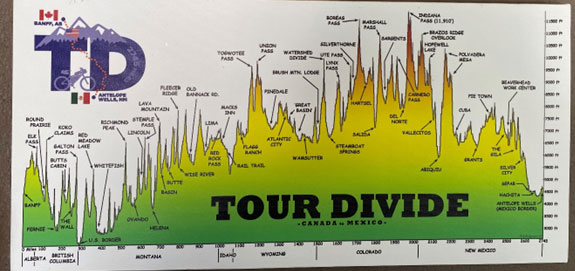

The Continental Divide represents an imaginary line running South to North along the Rocky Mountains from Mexico to Canada where the water runs into the Pacific on the West of the line and into the Atlantic or Gulf of Mexico on the East of the line. The cycling route attempts to follow this line as closely as possible and therefore spends the majority of the time high in the mountains on remote dirt roads and occasional single track mountain bike trails. There are two cycle routes and one walking trail. The two cycle routes are very similar and have a lot of common roads. The route called the Tour Divide is a race route and the other is known as the Great Divide Mountain Bike Route which was devised by the Adventure Cycling Association (ACA) of the United States. The Great Divide (ACA) route was the route we had decided to attempt.

The route starts at a small border crossing between the USA and Mexico called Antelope Wells situated in the semi-desert of southern New Mexico and ends in Banff, a touristy ski and outdoor resort, in Alberta, Canada. The route has recently been extended North to Jasper but we decided to come off the route just after Banff and cycle to Calgary where we could pick up a flight for home.

The route goes through 5 States in America; New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, Idaho (briefly) and Montana and continues through British Columbia and Alberta in Canada.

How did we end up on this trail? The simple answer was a combination of; “it’s not Peru” and Sally didn’t quite realise what this trail involved until after we had booked the flights. Since retirement we have done 3 cycle tours of around 3 months and, having enjoyed the experience, were keen to do another. I was keen to go back to South America and visit Peru and cycle through the high passes in Coridilleras Blanca and also take in Machu Picchu, the huge salt flats in Bolivia and maybe include the Atacama Desert in Northern Chile. A quick knock up of a route soon showed this wasn’t possible in three months without including some bus journeys and that it was going to be a very tough ride with the added stresses of complicated logistics. Sally asked whether there were any others trips I was keen on in a hope to distract me from South America. I had always fancied crossing the United States by bike but wasn’t keen on cycling through the major cities on busy roads. Sally, seeing some weakening in my resolve and pointing out that there was some civil unrest in Peru, jumped at the chance and we started to research routes across America.

The ACA (the US equivalent of the CTC) have a number of routes across America both North-South and East-West some along the coasts and some in the mountains. We ruled out West-East routes as they had large expanses of flat arable land to cross that didn’t seem too exciting. Looking at North-South routes the choice was between the Pacific Coast & Sierra Cascades routes in the West or Atlantic Coast route on the East Coast or the Great Divide along the Rockies. The Great Divide was the only route that was primarily off road and would have the least traffic, towns and cities and would cover the most wilderness and hence have the best chance of seeing wild life and, of course, was mountainous which we prefer to the flat.

Sally was relieved to hear there was an alternative to Peru and liked the fact we would actually be able to converse with people without struggling with a foreign language and so we booked a flight to El Paso in Texas, the nearest international airport to Antelope Wells. We were committed to starting in June, just 6 months away, and doing the route South to North.

Now Sally took a greater interest in the You Tube videos I had been watching and slowly it dawned on her the severity of the under taking. The ACA summarise the route as:

“Ride the longest off-pavement route in the world.

The Great Divide Mountain Bike Route (GDMBR) is Adventure Cycling’s premier off-pavement cycling route, crisscrossing the Continental Divide in southern Canada and the U.S. This route is defined by the word “remote.” Its remoteness equates with spectacular terrain and scenery. The entire route is basically dirt-road and mountain-pass riding every day. In total, it has over 200,000 feet of elevation gain. Nearly 2,100 miles of the route is composed of county, Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and Canadian provincial unpaved roads. The remainder is 60 miles of singletrack trails and 950 miles of paved roads including close to 50 miles of paved bike paths.”

It took the ACA 2 years to devise the route between 1995 and 1997 and the popularity of the route has been steadily growing. As we watched more You Tube videos and looked at the route in more detail, we realised it was certainly going to be a challenge. The main challenges being:

- Heat – New Mexico in particular could be very hot with temperatures of 30-45 degrees during the day.

- Lack of water – there were several sections of the route where water was scarce, unreliable or non-existent. We also learnt that a lot of the fresh water was infected with Giardia and would need filtering and that the water near old mine workings should be avoided as it could be contaminated with heavy metals.

- Lack of re-supply points – there were sections of the route where there would be no opportunity to re-supply our food stocks for a couple of days or where the food that could be bought would be very limited.

- Remoteness – often the route was several days ride from a sizeable town that might have a bike shop or other amenities. If something went wrong with our bikes or our gear or ourselves, we would have to rely on our initiative to find a way to continue.

- Keeping safe from the wildlife – the number one concern was for Black and Grizzly Bears that inhabited most of the route but also, we needed to be wary of Moose, Bison and Rattle Snakes.

- Cold – we had to cross several mountain passes in excess of 10,000 ft where the weather could turn very bad so we needed to ensure we had sufficient clothing for that eventuality. We upgraded our sleeping bags and replaced our tent with a second hand but hardly used equivalent.

- Wet – we heard numerous stories of how tracks deteriorated to impassable “Peanut butter mud” if it rained. I decided to remove the mud guards from our bikes as they would only get clogged up if we encountered these conditions.

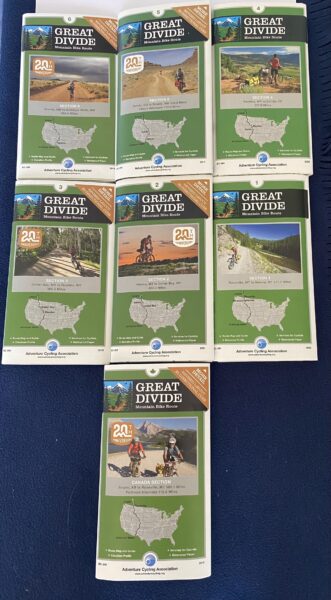

- Route finding – the route is not way marked; I think we saw 2 or 3 signs on the entire route. The ACA provide 7 very helpful maps which we bought but at a scale of 1:200,000 these would be hard to follow should our GPSs fail. We took two GPSs with the route broken down into 72 daily rides and 15 alternative route options and we also had the route on Komoot on our phones as a further back up. We also carried a compass in case all else failed.

- Communication – getting ‘roaming’ on our phones for 3 months was prohibitively expensive and we would often be out of phone or internet coverage. However, we were pleasantly surprised by how often very remote and small settlements did have WIFI.

- Wild Fires – these have become more common and much larger due to global warming over the last few years. We needed to be prepared to alter our route if necessary and to try and keep up to date with any fires to avoid getting cut off or surrounded by them. We also discovered that meths stoves, like the our trusted Trangia, were not allowed in the National Forests and Parks so we bought a one pot Jet Boil gas cooker.

The majority of people do the route from the North to the South. We decided to start from the South for several reasons. We preferred to finish the ride in Banff or Calgary where we could relax, recuperate and prepare our bikes for the flight home with all the amenities close by. The alternative, finishing at Antelope Wells in the middle of nowhere, would mean trying to arrange transport to the nearest airport; El Paso was 160 miles from Antelope Wells with no public transport options. In addition, we would not know exactly when we would arrive, making arrangements to be picked up in advance difficult. So, we decided to go South to North

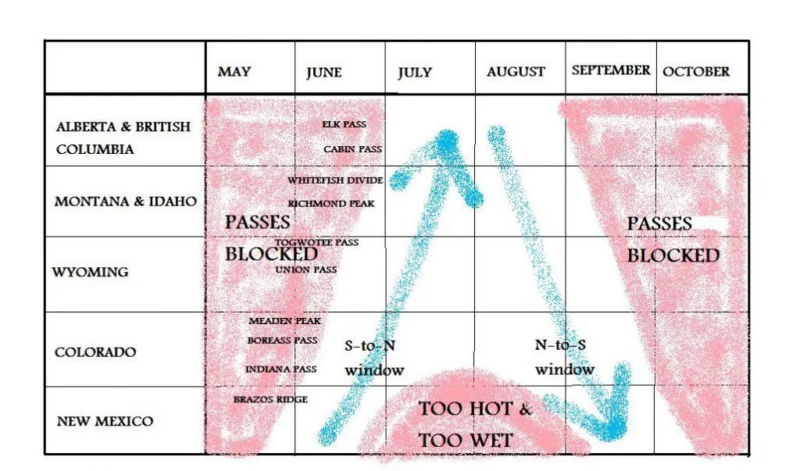

Next decision to make was when to go. After a bit of research, we came across the following graphic (by Mathieu van Rijswick). This shows the periods of time when the mountain passes are likely to be blocked with snow and also the periods when it is generally too hot or wet in the South.

To give us the maximum chance of avoiding the “peanut butter mud” in the south we needed to leave mid to late May and get through New Mexico before their wet season in July / August. However, what this graphic doesn’t show is New Mexico is huge and accounts for 700 miles, or a quarter of the entire route. Given other commitments, not least the Anerley BC Bike Trip to Wales, we decided to leave on the 4th June just a few days after returning from Wales, we were going to have to be organised!

Bears was the next topic to prepare for. There are bears along the entire route and we would be wild camping a lot of the time in the bear’s habitat so, despite it being a scary subject, it was one well worth researching.

| Bear populations | ||

| State / Province | Black Bears | Grizzly Bears |

| New Mexico | 5,000 – 6,000 | None |

| Colorado | 16,000 | None |

| Wyoming | Not known (but 500 in Yellowstone NP alone) | 600 |

| Idaho | 20,000 – 30,000 | 80 – 100 |

| Montana | 15,000 | 1,800 – 2,000 |

| British Columbia | 120,000 – 160,000 | 15,000 |

| Alberta | 38,000 – 39,000 | 1000 |

We googled how many people die from bear attacks in the United States; the average is about 3 per year. This compares more favourably than the 30 – 50 people killed by dogs per year in the United States (about 2 in the UK) or the 21 people killed by cattle in the United States (5 in the UK). Sadly, the number of fatal stabbings in London was 89 in 2021. So, all things considered we were probably in more danger staying at home than doing the Continental Divide. Dodgy statistical analysis but it made us feel better!

I read a book years ago that I had bought when we last visited Canada called “Bear Attacks there cause and avoidance”. It scared the living daylights out of me so I decided not to re-read it and watched a few You Tube videos instead.

The guidance boiled down to:

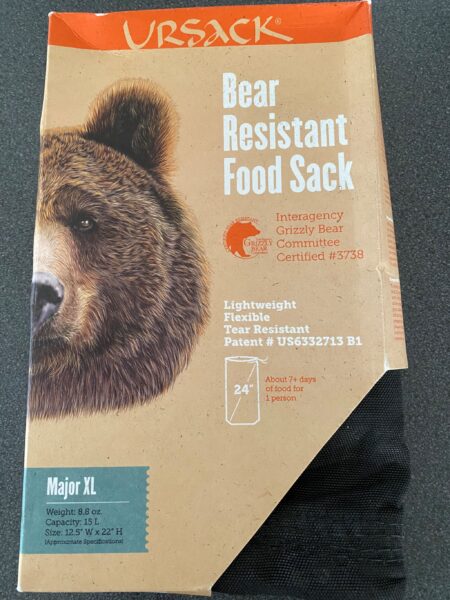

- Avoid encounters by making noise and not keeping food or any other items with a strong odour in your tent.

- Don’t camp if there signs of bears nearby; e.g. scratch marks on trees or bear skat on the ground.

- Have quickly accessible Bear Spray on you at all times.

- If you do encounter a bear; stand your ground, stick together, make yourself as large as possible and get your bear spray ready to use. Under no circumstances run, as this may trigger a chase response (easier said than done I imagine!).

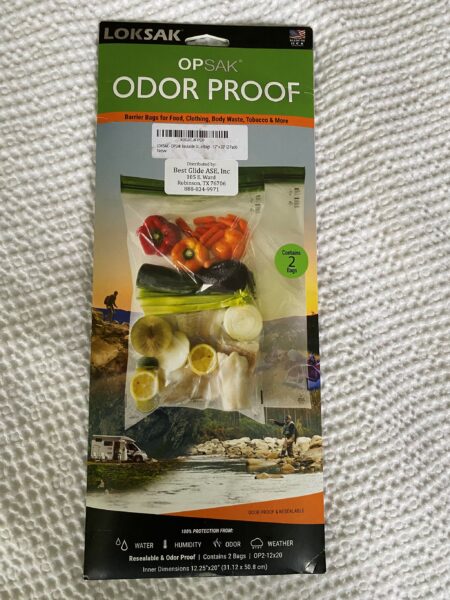

In response to this we bought odourless sealable plastic bags, very expensive bear proof bags for hanging our food in trees, carried a whistle, bought bear spray and bear bells (similar to the bells Morris Men use on their ankles) to attach to our bikes.

All packed up and ready to go we got a large taxi to take us to Heathrow and got through the stress of convincing the airline that our bikes could travel in large see through plastic bags. This was repeated when we got to Dallas to change flights but we arrived at El Paso safely with just one damaged bottle cage and proceeded to put our bikes back together in the airport.

Our paniers, tent and all our other luggage we packed in two old suitcases Sally had bought from a charity shop. We were worried about how we would dispose of them at the airport without attracting the attention of the police; who might have considered them “suspicious”. But in the end, it was easy; we asked a cleaning lady where we could dispose of them and she volunteered to dispose of them for us.

Bikes re-assembled we cycled 2 miles to an Air B&B, our accommodation for the next 2 nights. The next day we cycled to the shops to get Bear Spray, a new bottle cage, Gas canisters for our stove and food supplies. Stupidly we didn’t bother carrying any tools or spares to the shops and inevitably Sally got a puncture so we had to walk back in the blazing hot sun.

At dawn, on the second morning, a huge Ford pick-up truck arrived. It was relief that what we had arranged weeks before had actually gone exactly to plan. Our driver had long grey hair and an equally long beard and was 78. He had already driven 150 miles to pick us up, then he was going to drive 160 miles to our start point and then a further 140 miles home!

Just before mid-day we arrived at the border crossing and, after a few photos, waved goodbye to our driver.

There is nothing at the border crossing other than a couple of official buildings and a large wall that curves along the Mexican border across the landscape.

It was very hot, we were both were suffering from jet lag, headaches and all the anxieties about what lay in front of us so it wasn’t the most encouraging start.

The first stage was 45 miles on a flat, tarmacked road across scrubby semi desert so we made reasonable progress. We had been warned that there would be lots of Rattle Snakes in the first few days so we were quite wary of leaving the road for a pee. We developed a technique of stamping our feet and walking slowly trying spot any camouflaged snakes. Needless to say, we didn’t spot one. We were slightly disappointed not to get a photo. To our relief we did come across this rest area with his and her’s facilities although the privacy wasn’t great!

As we got nearer to Haticha (or our first night’s stop) we came across a bike painted white and decorated with flowers. Sadly, this was the bike of a cyclist that had ridden the Continental Divide from Canada but on this remote and quiet spot, just a few miles from finishing, had been the victim of a fatal hit and run accident. This seemed amazingly unlucky as we had only seen a couple of cars and a police border patrol all day.

Hatchita was a ramshackle settlement of derelict buildings and cars with a small petrol station and shop.

Our first night we slept in Community Hall for $5 with other cyclists. The hall was basic but provided camp beds, a kitchen and toilet.

Some cyclists were preparing to cycle to Antelope Wells for the start of the race (you can start from either end of the route), others were finishing the next day having “toured” down from Canada and others, like us, were newbies just setting off. We swapped stories and compared each other’s set up and kit. It was clear that we were carrying more than most, were the only ones to have panniers and not to have 29-inch wheels with at least front suspension. Everyone was younger than us although there were a couple of guys in their 50s. Sally was the only woman. We felt a bit like frauds but at least we had survived Day 1.